Library of Congress

MANY HANDS

A month and a half ago I attended a performance of The Nutcracker (Casse Noisette) at Les Grands Ballets here in Montreal. My daughter, who loves to dance to a recording for two pianos by Duo Benzakoun of Tchaikovsky’s music for this ballet, was enchanted. At the performance it struck me just how many hands go into creating and mounting this ballet: the story by Hoffmann, the score by Tchaikovsky, and the choreography by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, and the dancers, of course, but also the lighting technicians, the people who design and maintain the costumes, and the person who has to find and rehearse the children for their roles. It seems like—and probably is—a collective cast of hundreds. And all those hands have to work towards a common goal—a goal which, when the ballet was first mounted at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in December, 1892 was somewhat unclear. The precise way each movement, note, and stitch was to form a whole was out of focus. This comes from the artists seeing the whole, but this also comes from the audience knowing what should be there, like a phrase in Mozart that is resolved. Now, the choreography, the characters, and the music seem so familiar to us as to be obvious—as if there was no other way for them to fit together. But on that winter's day this was not the case. In fact, the first performance of what has now become ballet’s equivalent of Handel’s Messiah was a bit of a flop.

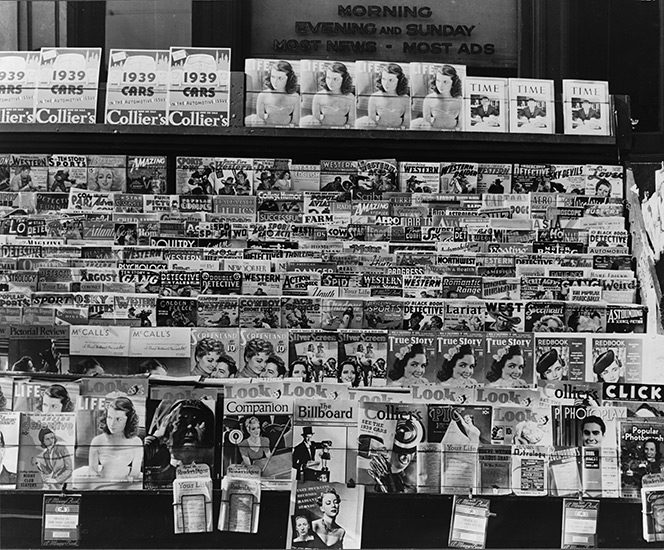

I am fascinated by this image of a large group of people groping towards something new. In my profession the analogue to the creation and mounting of a new ballet would be the launching, or the relaunching, of a magazine. Sometimes the launch is successful, and sometimes not. And this is because a magazine is both a circuit in society and to a great extent a living thing.

Both of these ideas might seem like a stretch. Think however what a magazine is: however published and produced it’s a bridge between one smaller group of people and another, larger group. And, the function of that bridge is to bring that second group novelty—news. It doesn't really matter if the "news" is the most recent trends in shoes or headphones, the most recent writing by Shiela Heti, or an essay on the shifting politics of Pakistan; it's all in a loose sense news. It’s a carefully chosen and crafted slice of the zeitgeist presented to an audience. The groups that are brought together could be manufacturers and consumers as much as writers and readers, but they're still being brought together.

With each issue the act of finding, editing, and presenting a compelling piece of the here-and-now has, to some extent, to begin again. Making a magazine is a constant quest for things that no one has thought of yet, or things that have been forgotten yet are, out of the billions of ideas out there, important now. This constant quest for the new angle, the thought that balance between common knowledge and the unthinkable is the rarest of fuels to fly on.

While we know now what the New Yorker or Wired "is"—what their supporting ideas are, and what we'll get when we pick up an issue—we take this knowing for granted. For that certainty is the result of a complex collaboration between readers, circulators, editors, advertisers, printers, and writers, a certainty that seems obvious now, but was not when either of these magazines started. The day before these magazines hit the newsstands, no one in the general public knew that they needed either of them in their lives. And while the New Yorker had a bumpier launch than Wired, in each case there was a lot of groping to discover who the audience was and what they wanted. As a counterexample consider George, the magazine launched with much fanfare by the late John F. Kennedy, Jr.. What was “Not politics as usual?” Unfortunately, the audience and the message were still groping towards each other when the publication folded in 2001.

When I have been involved in launches or redesigns, I tend to think of the design as having two stages: a overgrown bush phase, and a neat topiary phase. At first, editors and designers are figuring out whether each element is the right size, and how they fit together; later, unused departments and design behaviours are clipped away, leaving a piece of design that seems like its always been that way, like it has a life of its own. It’s a “life” that a painting has for a painter: at some point the artwork directs the artist. At some point writers and editors and readers instinctively know what a Talk of the Town piece is, and what it should be.

The feedback loop for this act is tenuous: once every week or month, the magazine receives newsstand circulation numbers that are three or four months old. Venues like the iTunes store tried to change that, and website traffic can (perhaps) offer some indication of how popular an issue will be, but the bottom line is only a number, and one that is generally out of sync with where everyone on the production side is at that particular moment. There's a gap, in many ways a profound one, between the creators and the audience, in terms of feedback. It's as if a magazine is a ballet which is danced to an empty hall, but filmed. There is bubble between creation and reception. The audience knows if the work as a whole is right, but while it's being created all the dancers have to go on is the ideas, the models, they have in their heads.

Many thanks to Jared Bland

February, 2013